Translated and Sourced from Mizuki Shigeru’s Mujyara, Kaii Yokai Densho Database, Japanese Wikipedia, and Other Sources

In Japanese folklore, if you make a promise you had better keep it—even if you are the Emperor of Japan. Otherwise, the person you betrayed might hold it against you and transform into a giant rat with iron claws and teeth and kill your first-born son. That is the story of the Emperor Shirakawa, his son Prince Taruhito, and the Abbot of Miidera temple Raigo—better known as Tesso, the Iron Rat; or more simply as Raigo the Rat.

What Does Tesso Mean?

The kanji for Tesso is about as straight-forward as you can get. 鉄 (te; iron) +鼠 (sso; rat). The name Tesso was given to this yokai by artist Toriyama Sekien in his yokai collection Gazu Hyakki Yako (画図百鬼夜行; The Illustrated Night Parade of a Hundred Demons,), although the character is much older.

Toriyama’s Text: The Abbot Raigo transformed into a monsterous rat.

Tesso is different from many yokai in that he is a singular character. There is only one Tesso. Until Toriyama came up with the much cooler name for his collection, Tesso was known as Raigo Nezumi (頼豪鼠), meaning Raigo the Rat.

The Story of Raigo the Rat

The tale begins with the Emperor Shirakawa, who was desperate for an heir to his throne. He enlisted the aid of the Abbot of Miidera temple, a powerful Buddhist monk named Raigo. Emperor Shirakawa promised Raigo vast rewards if he could use his spiritual powers to give the Emperor a son. Accepting the offer, Raigo threw himself into meditation and prayer and magic. Soon enough a son was born to Emperor Shirakawa, the Prince Taruhito.

Raigo went to the Emperor for his promised reward, and asked only for the funds to build an ordainment platform at his temple of Miidera. The Emperor was too happy to oblige, until temple politics interfered.

Miidera had a rival temple, the powerful Enraku-ji in Mt. Hiei in Kyoto. The monks of Enraku-ji were not normal, peaceful monks, but a terrible army of militant warriors feared across all Japan. It was said the Emperor could influence all on Earth except three things—the blowing of the wind, the rolling of dice in a cup, and the monks of Enraku-ji. Even though they were both of the Tendai sect of Buddhism, Miidera and Enraku-ji has split into different factions after the death of their founder. Enraku-ji was not about to allow new Tendai monks to be ordained at Miidera, a privilege they reserved for themselves.

The Emperor had no choice but to break his promise to Raigo. He asked if there was anything else he could give, but Raigo was adamant. So adamant, in fact, that he went on a hunger strike and died after 100 days, cursing the Emperor with his final breath. At the house of his death, a figure in white was said to have appeared beside the cradle of the 4-year old Prince Taruhito, who died soon afterward. What Raigo had given, Raigo had taken away.

What happened next was strange—up until now this is the usual ghost story with Raigo returning as a yurei. But the tale does not end there. Raigo used black magic to ensure he was reborn after death as a dread yokai. He twisted his body into the form of a giant rat as large as a man, with a body as strong as stone and with claws and teeth or iron.

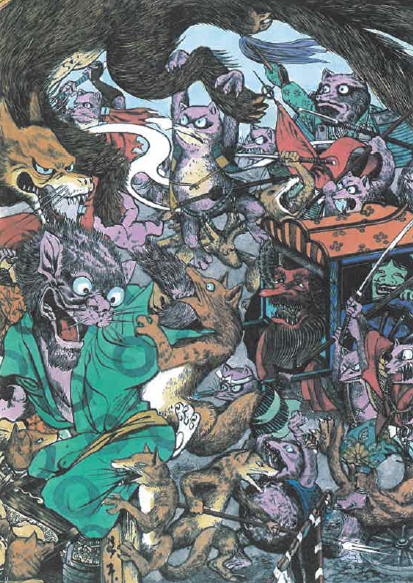

The newly-named Raigo the Rat invaded Enraku-ji with an army of rats, devouring their rare and valuable Buddhist scriptures, and even eating statues of the of the Buddha himself. This reign of rat-terror when on until a shrine was built to appease Raigo, transforming him from a deadly emissary of vengeance into a protecting kami spirit. Because that’s how evil spirits roll in Heian-period Japanese folklore.

Raigo the Onryo

Old texts describe Raigo as an onryo, the name for the grudge-bearing spirit popular in Japanese horror films. Raigo wouldn’t be seen as an onryo nowadays—his transformation into a rat makes him more of a monster than a ghost. But in the Heian period the word onryo had a more specific meaning, being something with a grudge against the Emperor of member of the Imperial family. And that label suits Raigo just fine.

Raigo and the Heike Monogatari

The story of Raigo comes from the Heike Monogatari (平家物語; Tale of the Heike) an epic poem from the Heian period that tells of the Heike/Taira wars that split Japan as two factions struggled for the throne. The Heike Monogatari is often called Japan’s version of The Odyssey, freely mixing historical fact with the supernatural and mythological.

Because the Heike Monogatari comes from an oral storytelling tradition, there are multiple versions of it with variations of the story of Raigo the Rat. In one of the older versions—the Engyo Hon (延慶本; Book of the Engyo Period), the story ends with the death of Prince Taruhito. In later versions Raigo gets more and more monstrous. The 48-volume Genpei Seisuiki version has Raigo attacking Enraku-ji with his army of rats, and in the 14th century historical epic Taiheiki (太平記; Record of the Great Peace) Raigo is described as having a body of stone and claws and teeth of iron. This Raigo ate not only the sacred texts of Enrakuji, but also their statue of Buddha.

Other Tales of Raigo

Raigo the Rat was a popular enough character that other writers continued the story after the Heike Monogatari. For example, a collection of Tanka poems from Otsu city, Shiga prefecture called Kyoka Hyakumonogatari (狂歌百物語; A Hundred Stories of Satirical Poems) featured the poem Raigo of Miidera and retold the story from the Heike Monogatari.

During the Edo period, author Gyokutei Bakin wrote the story Raigo Ajari Kaisoden (寺門伝記補録; The Tale of the Abbot Raigo who Transformed into a Monsterous Rat), illustrated by famous ukiyo-e artist Katsushika Hokusai.

Gyokutei puts Raigo into a different historical narrative, telling the story of Shimizu Yoshitaka (also known as Minamoto no Yoshitaka), the orphaned son of Minamoto no Yoshihara. Yoshitaka was on a pilgrimage of holy sites when he had a vision of the Raigo, who told Yoshitaka he would teach him the secrets of black magic and help him amass an army to take vengeance against his father’s killers. All Yoshitaka has to do is write an official request for help, and place it before Raigo’s shrine along with a donation.

Yoshitaka does as requested (of course), and soon finds himself in possession of Raigo’s shape-changing ability and mastery over rats. As an additional twist, Yoshitaka is hunted by Nekoma Mitsuzane (who’s name ironically begins with the kanji for “cat” in a traditional cat-and-mouse game). In one scene, Nekoma finds Yoshitaka and is about to kill him when a massive rat leaps to Yoshitaka’s defense. In another scene, Nekoma is torturing Yoshitaka’s mother-in-law and Yoshitaka leads and army of rats to her defense, saving the day.

Hundreds of years later, Raigo still has a hold on the popular imagination. Modern author Kyogoku Natsuhiko used the story of Raigo as the basis for his mystery novel “Tesso no Ori” (鉄鼠の檻; The Cage of the Tesso).

The Historical Raigo

Although the tale of Raigo the Rat is fictional, most of the key players are historically verified. Shrine records show Raigo was the Abbot of Miidera, and at one time petitioned Emperor Shirakawa for funds to build an ordination platform—a petition that was denied. There is little doubt that rival temple Enraku-ji played some hand in the denial. At the time, Enraku-ji’s power was absolute.

The only person not involved in the affair was Prince Taruhito. Records put the young Prince’s death in 1077, while Raigo himself died in 1084. This contradicts the facts of the legend.

Rats, of course, were an actual source of fear to the fragile book collections of temples across all of Japan. So it is no wonder that a double-punch of an angry spirit and a scroll-eating rat was a natural mixture for Kaidan.

Tesso Shrines

There are a couple of supposed shrines to Raigo, each claiming to be THE shrine that ended Raigo’s scroll-devouring revenge.

In Hyoshi Taisha, in the Sakamoto district of Otsu city, Shiga prefecture, there is a shrine called the Shrine of the Rat that some connect to Raigo. Shrine records, however, say that the shrine is dedicated to the Rat God of the Chinese Zodiac and not to Raigo.

Miidera shrine has the most obvious connection, and has a small monument and shrine dedicated to Raigo also called the Shrine of the Rat. This shrine faces directly at Mt. Hiei in Kyoto and is said to be placed in defiance of Enraku-ji’s role in Raigo’s curse.

However, Mt. Hiei has their own shrine—the Shrine of the Cat—that looks directly at Miidera. Some suspect the two shrines are connected by an older legend of a monk who summoned a giant cat to destroy a giant rat that was menacing the area.

In truth, probably both of these Shrines of the Rat were re-dedicated to suit interests in the story. Like Relics in Catholic churches, a shrine or artifact connected to a popular legend can mean tasty tourist dollars and neither Buddhist temples nor Shinto shrines never let the facts get in the way of a good story. Especially one that attracted tourists.

Translator’s Note:

This was translated for Mike Mignola, who picked out Tesso from a copy of Mizuki Shigeru’s Mujyara that I showed him at Emerald City Comic Con. Mignola liked the illustration of Tesso, and I am only too happy to give him the story behind the image.

Plus, I did a lot of cats last year. It is only fair that at least one rat gets to appear as well.

, An Account of the War in Rabaul by Mizuki Shigeru (Mizuki Shigeru no Rabauru Senki), and the touching Account of War from Father to Daughter (Mizuki Shigeru no Musume ni Kataru Otosan no Senki) that he wrote for his daughter Etsuko.

, An Account of the War in Rabaul by Mizuki Shigeru (Mizuki Shigeru no Rabauru Senki), and the touching Account of War from Father to Daughter (Mizuki Shigeru no Musume ni Kataru Otosan no Senki) that he wrote for his daughter Etsuko.

,

,  ), Mathew Meyer (

), Mathew Meyer ( ), and–humbly–myself, Zack Davisson (

), and–humbly–myself, Zack Davisson ( , upcoming Yurei: The Japanese Ghost).

, upcoming Yurei: The Japanese Ghost).

. Is there a yokai-inspired comic in Seifert’s future? I suggest you keep an eye out on your local comic shop!

. Is there a yokai-inspired comic in Seifert’s future? I suggest you keep an eye out on your local comic shop!

from Drawn & Quarterly. Kitaro—known as Gegege no Kitaro in Japan—is THE yokai manga, created and written by Japan’s most eminent yokai scholar, Mizuki Shigeru. It is thanks to Mizuki Shigeru that yokai are still known and loved in Japan, and it is thanks to Gegege no Kitaro that this website even exits.

from Drawn & Quarterly. Kitaro—known as Gegege no Kitaro in Japan—is THE yokai manga, created and written by Japan’s most eminent yokai scholar, Mizuki Shigeru. It is thanks to Mizuki Shigeru that yokai are still known and loved in Japan, and it is thanks to Gegege no Kitaro that this website even exits.

) but I wrote all of the Yokai Files included in the volume. Matt Alt (

) but I wrote all of the Yokai Files included in the volume. Matt Alt ( ) wrote the introduction talking about Mizuki Shigeru’s legacy and place in Japanese culture.

) wrote the introduction talking about Mizuki Shigeru’s legacy and place in Japanese culture.

and

and

:

: